Why do horses need dentistry?

Assoc Prof Gary Wilson

School of Veterinary Science, University of Queensland

Evolution of the horse

As the horse evolved from a small forest dweller (55 million years ago) to a larger animal foraging in open country, the diet also changed from succulent foods to a drier coarse diet. The early horse ancestors were browsers (as opposed to grazers) which fed on soft leafy vegetation and ferns. The cheek teeth were short-crowned (brachydont) similar to humans with no reserve crown (a reserve crown below the gum allows long-term eruption as the tooth wears away). These teeth were slow to wear away with this diet type and fossil records suggest that maximum life expectancy was 4 to 5 years due to tooth wear.

Around 20 million years ago, grasslands became a dominant plant type in North America where the horse was evolving. The diet of horses gradually changed from browsing to grazing the abrasive pastures. The horse also increased dramatically in size during this time.

The increase in body size created the need for a greatly increased intake of food. Consequently, a more efficient mastication process developed.

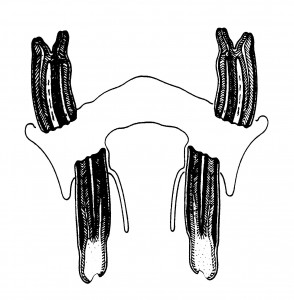

The newer coarse grazing diet caused an increased rate of wear of the teeth. To compensate for this, a system of almost continual eruption evolved. The cheek teeth became high-crowned (hypsodont) with most of the crown still under the gums (reserve crown). The reserve crown developed with a covering of cementum to allow for this continued eruption. These teeth could now erupt slowly over a long period of time to compensate for the surface of the tooth being worn away. Eventually though, these teeth would still wear down to the roots and become worn away but the life expectancy of the horse increased to around 20 to 25 years.

Figure 1: Young cheek tooth showing erupted crown (black arrow), reserve crown (white arrow) and developing roots (red arrow).

Figure 2: Old cheek teeth with no reserve crowns

The teeth also underwent enamel infolding (folding of the enamel of the tooth which increases the amount of enamel at the exposed surface) which also slows the rate of wear. The cheek teeth underwent molarisation [all similarly shaped with each possessing enamel ridges as a result of the infolding] with all cheek teeth tightly packed together. This results in the cheek teeth acting as a single grinding unit. Hence, any abnormalities which disturb this “single” arcade will have dire consequences.

Figure 3: Cheek teeth arcades with teeth in close contact forming a “single” unit.

Studies of wild horses grazing poor quality pasture (which is the normal evolutionary diet) show that they graze for 16 to 18 hours per day. This is done with the head down and wide side to side chewing excursions (lateral excursions). It has been estimated that the horse chews at a rate of 11 chews per 10 seconds. This all adds up to a lot of chewing of abrasive material which will wear the teeth evenly at a rate that eruption of the reserve crown can compensate for.

Normal occlusion

Normal incisor occlusion when viewed from the side shows the upper and lower teeth in perfect alignment at the front (rostral) edges when the head is down in the grazing position. This is not true when the head is raised as the bottom jaw (mandible) can move back and forth as the head is raised and lowered (by up to 1 cm).

Figure 4: Normal head position when grazing.

The upper jaws are wider than the lowers by approximately 30% (anisognathism). This results over time in a sloping cheek tooth surface which actually increases the surface area for chewing of the food.

Figure 5: Sloping occlusal surfaces of the cheek teeth due to anisognathism.

Why do we need to do equine dentistry?

Since the horse has become domesticated (hundreds of years), man has realised that dental problems have occurred. Our domestic horses don’t graze for 16 hours per day constantly (they don’t need to either because our pastures are too good or we feed them individual feeds of concentrates etc.). This dramatically reduces the normal rate of wear of the teeth. If concentrates are fed or the horse is fed from a bin on the stable door, the problems are exacerbated (head raised with chewing and the teeth are out of alignment due to the bottom jaw moving back). Concentrates result in an up and down chewing pattern instead of the side to side pattern (reduced lateral excursions).

This reduction in normal wear causes overgrowths or projections (commonly called sharp enamel points). These will cut the soft tissues of the cheeks causing painful ulcers. Normal preventative dentistry will address these sharp points and allow the horse to return to comfortable chewing and riding.

Figure 6: Sharp enamel points on the upper cheek teeth with resultant cheek ulcers.

Many other dental conditions can develop in our domestic horses. Routine dentistry by your veterinarian can detect these early and treatment and preventative measures then undertaken to correct them.

Wolf teeth in Horses

Gary Wilson

Photo 1 – Wolf tooth

In horses, the first premolar teeth, if present, are known as wolf teeth. No one is truly sure how this term originated but several theories abound and the term can be found in textbooks from the late 1700s.

Photo 2 – Upper wolf teeth (arrowed)

The wolf tooth is a vestigial tooth which is estimated to be present in up to 70% of horses and the tooth serves no useful purpose. It is most frequently a small tooth and it has no deciduous form (baby tooth). The wolf tooth, when present, usually erupts between 5 to 7 months of age and does not continue to erupt over a long period of time (the functional premolars and molars erupt over many years to balance the continual wear from grazing pastures).

Wolf teeth are common in the top jaw (maxilla) but can infrequently occur in the bottom jaw (mandible) as well.

Photo 3 – Lower wolf tooth (arrowed)

Wolf teeth may or may not be causing problems for the horse. They perform no function but may become painful if the bit contacts them. They also get in the way of being able to adequately contour the 2nd premolars (= bit seating the first cheek teeth) and certainly get dental disease associated with them. For this reason they are usually extracted in the ridden horse.

Photo 4 – Upper wolf tooth in a skull with food impaction causing periodontal disease

Extraction is done with the horse sedated and local anaesthesia infiltrated around the tooth (or occasionally a regional nerve block is given). The tooth is then removed painlessly.

Photo 5 - Local anaesthetic injection for wolf tooth extraction

Some wolf teeth can be quite large whilst others are very small. Unfortunately, the size of the exposed tooth crown gives no idea as to the size of the root of the tooth.

Photo 6 – Upper wolf tooth

Photo 7 – Tooth extracted from previous horse

Photo 8 – Small wolf tooth

Photo 9 – Tooth extracted from previous horse

Occasionally unerupted wolf teeth (blind wolf teeth) are present and are associated with a painful region in the gap between the cheek teeth and the incisors. These are removed surgically.

Photo 10 – Blind wolf tooth (arrowed)

Photo 11 – Tooth removed from previous horse